The Binding of Isaac, cords of love?

“Take your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac, and go with him to the land of vision, Moriah, and offer him up as a burnt offering” Gen 22:2 How could a father attempt murder of a longed-for, beloved child at the command of a loving G8d? This is a question many have tried to answer. One tradition sees Virtue in Avraham’s willingness to sacrifice his child in obedience. Another tradition, however, as Rashi quotes in midrash, says this last of ten “tests” that challenge Avraham is Satanic. The accuser, Satan, challenges Avraham’s love of G8d, who enacts the test. According to the Midrash, Satan then descends to earth trying to talk Avraham out of the sacrifice, using all the reasons we would argue today. Avraham in mystical tradition represents the sphirah of “chesed” loving-kindness. Why does Avraham listen to the command to offer up his “only” son as a burnt offering? Was it fear, pure faith?

I propose another interpretation: the binding of Isaac is a parable about the sacrifices we make to honor our parents, in obligations borne of love. This is more consistent with the themes of love and strength in Genesis, and bears powerful wisdom for our lives today. According to Maimonides, Abraham does everything for the love of G8d and humans, who are in the Divine image.

“Scripture says (Deut. 11:13): ‘To love the Lord

your God’-whatever you do, do it only out of love.”…

Abraham our Father achieved this level; he served God out of love. ~Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Helek Introduction to Chapter ten of Mishna Sanhedrin

Avraham is the model of hospitality, his tent was always open, he interrupts an audience with the Divine to feed and wash the feet of three strangers, who reflect G8d’s image (when he is 90 and recovering from circumcision!) He plants an “eshel”, interpreted to mean an orchard or a hotel, to feed people, and teach them that bounty comes from G8d.

If Avraham is all about love, how can this be harmonized with attempted murder of Isaac? Consider this: love is the rope that binds his son. I have a newborn grandbaby, and it is stirring strong memories of motherhood. When that baby cries, you are bound to respond. A parents’ life is not their own. Mara Benjamin, in her article “The obligated Self: Maternal Subjectivity and Jewish Thought” brilliantly uses the experience of maternal obligation out of love to speak of religious obligation, a concept we are sometimes uncomfortable with. She writes

Maternal obligation, in both its practical and its existential dimensions, offers contemporary Western people’s most substantive experience with the meaning of obligation. …The care for an infant perfectly captures the pairing of command and love at the heart of rabbinic thought. If God is not only loving parent but demanding baby, we may find within ourselves the resolve to meet the demand.

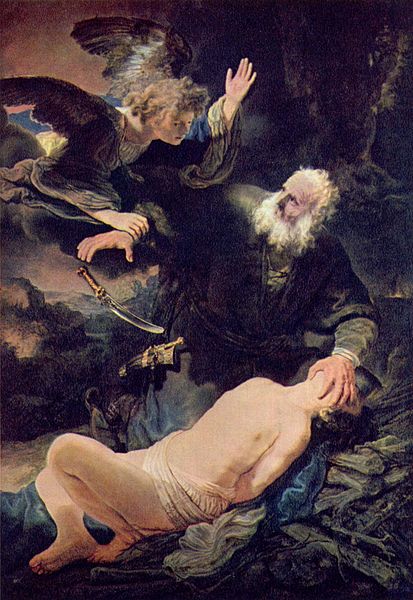

But what of caring for aging parents (or other relatives), is that not also an obligation bound by cords of love? According to tradition, Isaac was 37 at the time of his near sacrifice. (Based on his mother Sara’s age at his conception, 90 and the timing of binding of Isaac immediately preceding her death at 127 years) Avraham was 137 years old. In my mind I halve all the ages in the Avraham saga to make it relatable, still he’s elderly, perhaps disabled. Somehow he makes a three day journey on to mount Moriah and climbs a mountain. Although the donkey may carry him to the foot of the mountain, how does he climb, when the donkey is left behind at the foot of the mountain: Does Isaac carry him? I have recently had to put my life on hold to care for a disabled relative, I did it out of obligation borne of love. It is difficult, and my actual identity at times seemed subsumed by the obligation. I propose that, as many adult children Isaac is a care-giver whose obligation to care for his father is the rope that binds him. This makes sense of the ages of Avraham and Yitzhak, of the love that Avraham is said to embody. What about Yitzhak, named for the laughter of his elderly parents? He represents “gevurah” or strength in tradition, and it takes so much strength to care for aging parents. These obligations bind us but should not slay us. Avrahram responds to G8d’s call, lifts up his eyes to see the miraculous ram, that takes the place of his son so that Isaac can be a link in the chain of generations.

Isaac embodies the fifth of the Ten “Commandments” at Sinai: Kabed et avicha v’et imecha… honor your father and your mother, that you may long endure on land. According to Sefer Hamitzvot command “honor” means to give them to eat and drink, bringing in and taking out” This sounds like being a caregiver to an elderly disabled parent! According to Ramban, to honor parents is to honor G8d.